As a personal trainer for both strength and calisthenics, every so often I get asked the question:

“Hey Joel, is X good for strength training and fitness?” My answer, regardless of the tool, tends to be the same, and oftentimes, an unfavorable response to the person asking the question.

“It depends.”

If we revisit the article titled “Rubber Bands: Adding Bounce or Cutting Slack for Strength Training?” you will be reminded that strength is specific. Specificity, more specifically the S.A.I.D (specific adaptation to imposed demands) principle (see what I did there guys?), is central to improving whatever pursuit you are engrossed in. As a quick recap, it basically states that what you do, you improve at; therefore, doing chin-ups is the best way to improve at chin-ups, for example. Due to this principle, I will always, always, always answer, “It depends,” and elaborate.

Why does it depend on the situation? More often than not, the original question is not specific enough in and of itself. A better way to ask or phrase the question would be:

“Hey Joel, my goal is to improve at X in the upcoming months. Do you think using this piece of equipment is the most specific way for me to do improve at X?”

By being asked the question in this manner, I have your goals in front of me and am able to compare the equipment you are using to the progress or changes you want to occur for different muscle groups and your overall fitness level and muscle strength. Heck, you can do that yourself pretty well 9 times out of 10. So, now that we have clarified our question, “Are bands for strength training the most specific way to improve at what you are currently training for?” I have to give you another dissatisfying answer: Unless explicitly stated, I do not know what you want to improve and can’t answer you specifically. So instead, let’s look at the adaptations that banded strength work elicits and you can hopefully answer the question yourself.

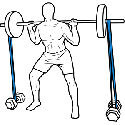

The adaptations that can be created and help build muscle in a variety of the major muscle groups by banded strength training (assuming we are using bands like these https://www.rubberbanditz.com/info-center/powerlifting-bands/ and not therabands, etc.) are as follows:

1) Increased total time spent accelerating the bar when banded (due to elastic resistance bands increasing as the movement gets closer to the top).

2) Joint angle specific strength (creation of more isometric strength closer to the top of the movement, for example at 60 vs 90 degrees in a banded squat scenario, as seen in Andersen et al. (2015)).

3) Stronger eccentric muscle loading and briefer transitory period (which is said to neurologically mirror plyometric training, seen in Siff (2003)).

4) Greater improvement in repetition strength (the ability to do more reps over a given period of time).

5) Greater improvements in constant load strength.

These five adaptations all focus in on a specific time that is especially beneficial to use workout resistance bands for muscle strength training: when you are aiming to get stronger at being faster. With raw strength gains similarly equated for weights only vs weights and banded training, banded training can definitely provide an edge when looking to be faster and more athletic. This is because a majority of (team) sports (excuse the broad generalization) move at joint angles closer to 60 degrees than 90 degrees, involve high repetitions of similar movements, and involve some form of acceleration -- these are all specific adaptations created by banded training. This is where we see that clarifying the question being asked is extremely helpful and allows things to make logical sense, rather than being unsure and needing to further search or understand the question. Read more in our related article and learn an additional 5 sneak times to use your resistance band.

Another point to consider here is the hierarchy of reducing specificity. This basically states that if you do something “broader” (think an ass to grass squat), something more specific (think quarter squat) has already been achieved within the realm of the broader thing being done. Flip this over and we quickly see that a good quarter squat definitely does not guarantee a good full depth squat. It comes as no surprise that a training program for higher acceleration and/or more velocity will transfer to slower movements and velocity as it follows a similar principle.

Accessed from: https://www.strengthandconditioningresearch.com/perspectives/conventional-weights-best-athletes/, Access date: 29/09/18.

Even if you are not training for specific speed or velocity gains, there is no harm in trying this method of training as it does transfer back should you not find speed of a large concern to you. It could, in fact, improve results as everybody’s body responds differently to different stimuli; you could be a person that does really well training with elastic resistance bands. With all this being said give it a try at least to see if it works well for you.Only results can really give you that information.

Accessed from: https://www.strengthandconditioningresearch.com/perspectives/conventional-weights-best-athletes/, Access date: 29/09/18.

There are also scenarios in which banded work is good as an addition or accessory to primary work. Most of the research discussed above is with regards to substituting weight machines and standard free weight varieties of squats, deadlifts etc. with banded varieties. As such, we should also consider the possibility that we might do our primary exercises normally and use some of the banded work as accessories. Should this be the case, our approach, “strength is specific,” does not change. We would still choose band exercises that highlight our specific weaknesses (for example banded close skull crushers if we struggle to lockout with a triceps extension during triceps exercises for triceps strength. In this case, experimenting with the volume, frequency and exercise selection, much like we would in the first place with banded work, is the only thing that can definitively tell you if what you are doing works as well as it can. Learn more in our related article about using a fitness band during squat training and making noticeable improvements on your handstands with resistance bands.

Enjoy testing and getting to know yourself better!

References and Acknowledgments:

Andersen, V., Fimland, M. S., Kolnes, M. K., & Saeterbakken, A. H. (2015). Elastic Bands in Combination With Free Weights in Strength Training: Neuromuscular Effects. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 29(10), 2932.

Chris Beardsley. Why are strength gains external load type-specific? (strength is specific) https://www.strengthandconditioningresearch.com/perspectives/conventional-weights-best-athletes/.Accessed 29 September 2018.

Shea, J. Accommodating Resistance and Accentuation for Increased Power. https://athletesacceleration.com/accommodatingresistance.html. Accessed 29 September 2018.

Siff M. (2003). Supertraining. 412.