Rubber Bands: Adding Bounce or Cutting Slack for Strength Training?

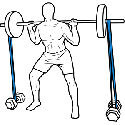

When you are at the gym training, you may see a guy or gal on a workout platform, squatting and/or deadlifting with exercise bands on either side of their barbell. This may be something you have never seen before and may seem a little different and interesting, and so the question arises:

Is what they are doing better than what I am doing? Will using those bands make me stronger and/or faster than I am now?

Before I answer this question for you, allow me to clarify a couple of things.

To start, what exactly does “stronger” or faster” mean to you? I ask this question because strength is specific, if nothing else. Deadlifting will make you better at deadlifting, not shoulder presses. If you are looking to grow bigger muscles for aesthetic purposes (hypertrophy), you are aiming to do something somewhat different to being able to lift larger amounts of weight (although there are links, of course) -- this definition of “stronger” is different than being able to sprint faster than your opponent on a field. Therefore, first and foremost, you must know what type of muscle strength and/or speed you are aiming to achieve.

Now that we have addressed that disclaimer, let’s dive into how bands can be used to develop more strength (ability to move more total weight), speed (ability to produce as much force as quickly as possible), and injury control -- as these are the areas that resistance band exercises are most applicable.

Using Resistance Bands to Increase Strength

When looking to lift more total weight, intensity is crucial. Intensity is the amount of weight you are lifting relative to the most you can lift in the movement you are currently performing. Referring back to muscle strength being “specific,” if you want to build muscle to lift more weight, lift a little bit more weight than you did the last time you did the exercise or same movement. Simple enough, right?

So, when we look at people training for strength, both using bands and not, we see little to no difference in results, provided they are adding intensity to each session. Despite there being less weight on the bar when using bands, the weight increases as the bands’ elasticity comes into play. In this way, the body is exposed to similar loads, banded or not. One caveat to this is that some studies (for example Matta et. al., 2015) have found that less muscle is built when using banded weights exercises, even if similar strength gains seem to occur. This could be a long-term issue, as having more muscle to innervate or recruit is an important part of being as strong as possible. As such, despite there being no documented short-term differences to strength improvements, reductions in hypertrophy could potentially factor in over longer training periods and affect strength increases in longer periods.

Following this, bands can be used for short periods with no impediment to strength. There are cases where it has beneficial elements, such as for youth, where using bands will teach them to more aggressively accelerate a bar if they do not have the experience to understand what that feels like. Supramaximal eccentrics are another application of bands, where a lifter with good lockout or closing strength and acceleration can eccentrically load a movement with more than they might be able to lift out of the bottom of the movement alone. With this being said, overloading eccentrics are very muscle-damaging and take large amounts of time to recover from, so use these wisely. Another potential application or use of exercise bands is as accessory work, especially if a lifter struggles with lockout strength. Using a band in such cases forces the lifter to accelerate the bar for longer periods within each repetition, meaning they will likely generate more force towards the end of a lift if they practice banded accessory work, which will lead to a higher likelihood of locking out.

Using Resistance Bands to Increase Speed

As seen above, the use of resistance bandsshould be limited in some ways when considering raw strength. Towards the end of the previous segment, however, I mentioned that banded work may force lifters to accelerate the bar for a much longer period of time, as the band aims to slow the bar speed towards the top of the movement. This comes in handy for athletes looking to increase power and speed (e.g., sprinters, Olympic lifters, jumping and plyometric athletes). The usefulness of creating more acceleration towards the end of the movement for such athletes is that it creates the drive or rapid force that allows them to be more powerful and faster in shorter periods of time. What this all boils down to is Newton’s second law of motion:

Force= Mass x Acceleration

If two runners of equal mass are competing, but one can accelerate faster, they will produce more force, and, assuming the transfer of forces is equally efficient, will run faster. As such, using bands for power and speed development would be very wise and produce very useful results, because it will allow such athletes to improve their acceleration and therefore force production without necessarily adding on too much muscle mass that could slow them down. Read more in our related article: How to Use Resistance Bands for Speed Training.

Using Resistance Bands for Injury Control

Attached to this section is a disclaimer: I am not a therapist. I encourage anyone with an injury to seek out a therapist first, as this would ensure that you receive the right treatment and perform band exercises specific to your condition. Following this, however, resistance bands can be great for retraining lifters out of bad habits, and well as for rehabilitation and prehabilitation purposes.

As far as retraining of habits goes, bands can be used for RNT (reactive neuromuscular training). This is a fancy word that basically describes how the addition of a secondary vector to a movement can improve the overall performance of a movement. For example, hypothetical person Max struggles to track his knees over his toes on a squat. His knees end up inside the line of his toes and he isn’t able to vary his squat stance or produce a different movement pattern. If we place a band over both knees, effectively aiming to pull them together (which encourages the knees to collapse), Max will have a feed of sensory input that cues him into opening his knees by resisting that collapse. In this way, the band has helped Max understand HOW to better track his knees over his toes. Bands can be used similarly to retrain new patterns and provide the same sensory input to a variety of exercises, including lunges, push-ups, and deadlifts.

Tying it All Together

So, returning to your original question: is the person you saw at the gym performing resistance band exercises doing something that will make them stronger or faster than you? The short answer is no; you can be just as strong without bands. This is because strength is specific to increasing intensity over time, not necessarily a banded resistance exercise. That being said, exercise bands can be useful for overall power and speed production, rehabilitative purposes via reactive neuromuscular training, and filling gaps in existing strength. With the breadth of resistance exercise applications, they are all considerable and worthy options to use in your strength training with bands program from time to time to target your various muscle groups and help you build the strength and speed you want. Learn more in our related blog articles about 5 sneak times to use your resistance band